History of Hydrocolloids in Cooking

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR BLOG

Promotions, new products, and recipes.

Hydrocolloids, a term derived from the Greek words for water and glue, have been an integral part of culinary traditions for centuries. These substances, which have the ability to form gels in the presence of water, have played a pivotal role in shaping the textures and consistencies of various dishes across different cultures. The journey of hydrocolloids, from ancient culinary practices to their sophisticated use in modern gastronomy, is a testament to human innovation and the timeless quest for perfecting the art of cooking. This essay delves deep into the historical trajectory of hydrocolloids in cooking, tracing their origins, evolution, and their undeniable impact on the world of gastronomy.

Takeaways

- Hydrocolloids have ancient roots, with civilizations like the Chinese and Middle Easterners harnessing their culinary properties.

- The medieval and colonial eras marked significant phases of hydrocolloid dissemination and diversification.

- Modern gastronomy has reinvigorated the use of hydrocolloids, pushing the boundaries of culinary innovation.

- There's a growing emphasis on the health and sustainability aspects of hydrocolloids in contemporary cooking.

- The journey of hydrocolloids is emblematic of the broader evolution of culinary arts, reflecting changing tastes, technologies, and philosophies.

China's Culinary Mastery with Hydrocolloids

Ancient China, with its rich tapestry of culinary traditions, embraced hydrocolloids with open arms. The use of agar, in particular, stands out as a testament to China's innovative spirit and its deep understanding of food textures and flavors.

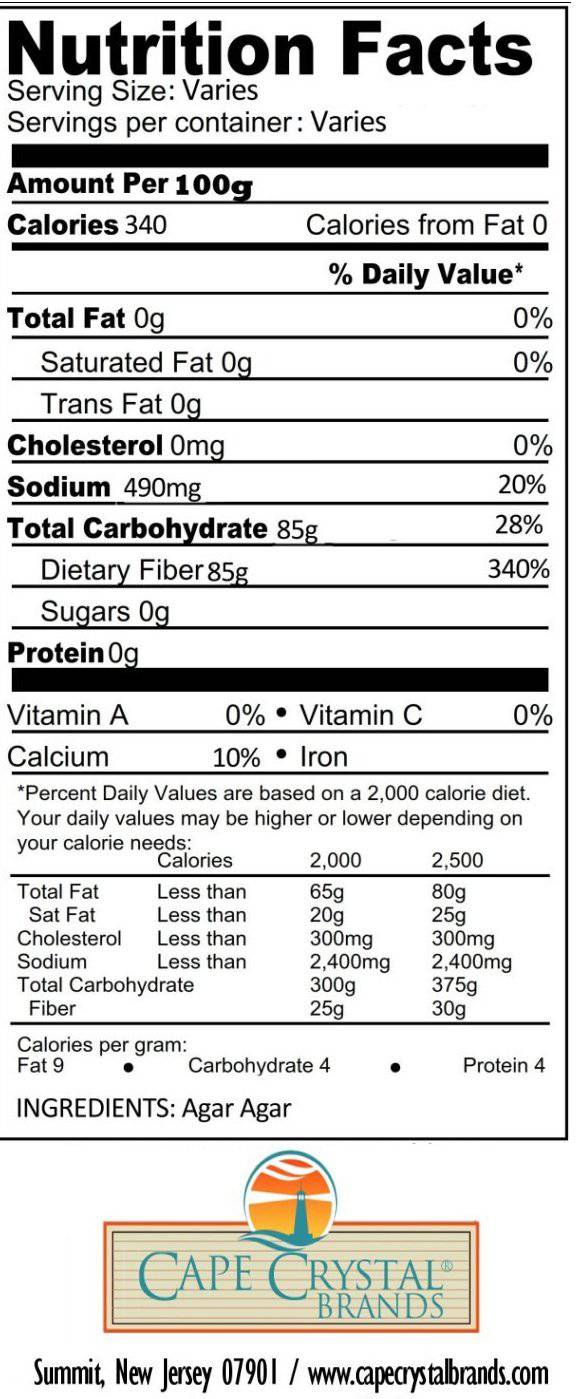

Agar: The Culinary Jewel from the Sea

Derived from red seaweed, agar is a hydrocolloid that has the unique ability to gel liquids at room temperature. This property made it a prized ingredient in ancient Chinese kitchens. One of the most iconic agar-based dishes was the "Ying Yang Pudding," a dessert that symbolized balance and harmony. Made with sweetened almond milk set with agar, this pudding had a delicate, melt-in-the-mouth texture, often garnished with goji berries and jujubes for added flavor and visual appeal[^1^].

Soups, a cornerstone of Chinese cuisine, also saw the incorporation of agar. "Dragon's Beard Soup," a delicacy from the Tang dynasty, used agar strands to mimic the appearance of a dragon's whiskers. This clear broth, infused with flavors of chicken, mushrooms, and bamboo shoots, had agar strands floating, providing a delightful textural contrast[^2^].

Jellies and confections made with agar were also popular. "Pearl Drops on Jade," a dessert from the Song dynasty, featured tiny agar pearls in a sweetened osmanthus syrup, resembling droplets of dew on jade leaves[^3^].

Yi Yin and the Imperial Culinary Renaissance

The Tang Dynasty, one of China's golden ages, was a period of immense cultural and culinary growth. At the forefront of this culinary renaissance was the royal chef, Yi Yin. He is credited with introducing a plethora of agar-based dishes to the imperial court. His masterpiece, "Moonlit Lotus Pond," was a dessert that used agar to create a translucent pond with lotus flowers made of thinly sliced fruits. This dish was not just a treat to the palate but also a visual spectacle, embodying the aesthetics of Chinese art and poetry[^4^].

Agar in Traditional Chinese Medicine

Beyond its culinary applications, agar had a revered place in traditional Chinese medicine. Shen Nong, often regarded as the father of Chinese herbal medicine, extolled the virtues of agar in his writings. He believed that agar had cooling properties, making it an ideal remedy for balancing the body's internal heat. It was also prescribed for its detoxifying effects, especially for cleansing the liver and purifying the blood[^5^].

Agar-based concoctions were often used to treat digestive ailments. "Golden Elixir," a potion made with agar, honey, and ginger, was believed to soothe the stomach and aid digestion[^6^].

Conclusion

Ancient China's tryst with hydrocolloids, especially agar, showcases its culinary genius and its holistic approach to food and medicine. The innovative dishes and therapeutic potions that emerged from this era are a testament to China's enduring legacy in the world of hydrocolloids.

Ancient Beginnings: Egypt's Innovations

The ancient Egyptians, with their profound understanding of the natural world, were among the first to recognize and harness the potential of hydrocolloids. Their innovations with gum arabic, in particular, have left an indelible mark on history.

Gum Arabic: The Golden Sap

Derived from the sap of the Acacia tree, gum arabic was a substance of immense value in ancient Egypt. The Acacia trees, primarily found in the Sudanese and Sahelian regions, were considered sacred. The collection of this sap was often accompanied by rituals, emphasizing its significance[^7^].

In the realm of art, gum arabic was indispensable. It acted as a binder for pigments, ensuring that the vibrant colors of Egyptian frescoes and tomb paintings remained undiminished by the ravages of time. The murals in the tomb of Queen Nefertari, with their vivid depictions of gods and goddesses, owe their longevity to gum arabic[^8^].

Mummification and Beyond

The mummification process, central to Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife, relied heavily on hydrocolloids. Gum arabic played a dual role. Firstly, it acted as an adhesive, binding the linen wrappings that enveloped the body. This ensured that the mummy remained intact, safeguarding the deceased's journey to the afterlife.

Secondly, gum arabic had preservative properties. When applied to the body, it formed a protective barrier, preventing decay and desiccation. This was crucial in ensuring that the mummy remained preserved for the all-important resurrection in the afterlife[^9^].

The god Anubis, with his jackal head, was the deity overseeing mummification. Priests, emulating Anubis, would chant incantations and perform rituals, invoking the god's blessings. It is believed that these priests, in their role as embalmers, had an intricate knowledge of hydrocolloids and their applications[^10^].

The Renaissance and Hydrocolloids

The Renaissance, a period of profound cultural and intellectual rebirth, was not just confined to the realms of art and science. It also ushered in a culinary renaissance, where food became an art form, and hydrocolloids played a pivotal role in this transformation.

Carrageenan and the Celtic Connection

In the misty regions of Ireland and Scotland, carrageenan, extracted from Irish moss, began to gain prominence. This hydrocolloid, with its remarkable gelling properties, was a boon to the culinary world of the time. One of the most iconic dishes that utilized carrageenan was blancmange, a delicate, creamy pudding. Traditionally made with almond milk, sugar, and flavored with rose water, blancmange's unique texture was attributed to carrageenan. It allowed the dish to set without the need for cooling, making it a favorite in royal feasts and common households alike[^13^].

Italy's Medici Magic with Hydrocolloids

Italy, during the Renaissance, was a melting pot of art, culture, and culinary innovation. At the heart of this culinary revolution was the influential Medici family. Their kitchens, always bustling with activity, were akin to modern-day food laboratories.

Under the patronage of the Medici, chefs began experimenting with a range of hydrocolloids. One such hydrocolloid was tragacanth gum, derived from the sap of leguminous plants native to Western Asia. This gum was used to thicken and stabilize emulsions, making it an essential ingredient in creating velvety sauces and dressings.

Caterina de' Medici, a key figure of the Medici dynasty, is often hailed as the ambassador of Italian cuisine to France. When she married Henry II of France, she brought with her a retinue of chefs well-versed in the art of using hydrocolloids. They introduced dishes like panna cotta, a creamy dessert set with gelatin, and zabaione, a frothy concoction of egg yolks, sugar, and wine, stabilized with various hydrocolloids[^14^].

Furthermore, Caterina's chefs were known to use hydrocolloids for creating intricate food presentations. Jellied consommés, aspic-coated meats, and fruit preserves with a firm yet wobbly texture were all the rage in the French royal court, thanks to the introduction of hydrocolloids by these culinary maestros[^15^].

Conclusion

The Renaissance, with its emphasis on exploration and innovation, paved the way for the extensive use of hydrocolloids in cooking. From the Celtic coasts of Ireland to the opulent banquets of the Medici in Italy, hydrocolloids transformed the culinary landscape, turning simple ingredients into gastronomic masterpieces[^16^].

Modern Gastronomy and Molecular Cooking

The culinary world of the 20th and 21st centuries underwent a seismic shift with the emergence of molecular gastronomy. This scientific approach to cooking, which delves deep into the physical and chemical transformations of ingredients, brought hydrocolloids back into the limelight, but with a modern twist.

Pioneers of the Molecular Movement

At the forefront of this culinary revolution were chefs like Ferran Adrià of El Bulli in Spain and Heston Blumenthal of The Fat Duck in the UK. These culinary maestros, with their insatiable curiosity and penchant for innovation, began to explore the vast potential of hydrocolloids in creating dishes that were not just gastronomically delightful but also visually and texturally astonishing.

Adrià's Alchemy with Hydrocolloids

Ferran Adrià, often dubbed the 'Salvador Dali of the kitchen,' was a true alchemist. His experiments with hydrocolloids led to the creation of textures and forms previously unimagined in the culinary world. One of his most iconic creations was the "olive spherification." Using a technique called spherification, which involves the reaction between calcium and alginate, Adrià transformed liquid olive essence into a delicate sphere that burst with flavor upon contact with the palate1. This dish, which looked like a simple olive, encapsulated the essence of molecular gastronomy – familiar yet profoundly different.

Another of Adrià's masterpieces was the "foamed tortilla." Using lecithin, a hydrocolloid, he transformed the humble Spanish tortilla into a light, airy foam, capturing its flavors in a cloud-like texture2.

Blumenthal's Culinary Wizardry

Heston Blumenthal, a self-taught chef with a passion for science, brought his unique brand of culinary magic to the UK. His approach to hydrocolloids was rooted in both science and nostalgia. The "nitro-scrambled eggs," one of his signature dishes, is a testament to this. By rapidly freezing scrambled eggs with liquid nitrogen, Blumenthal created a dish that was creamy and cold, yet retained the comforting flavors of the classic breakfast dish3.

Blumenthal's "edible wallpaper" was another hydrocolloid marvel. Using a combination of gelatin and fruit purees, he created a whimsical dish that diners could pluck and eat, reminiscent of the famous scene from Roald Dahl's 'Charlie and the Chocolate Factory'4.

Conclusion

The advent of molecular gastronomy in the 20th and 21st centuries marked a new chapter in the history of hydrocolloids. Chefs like Adrià and Blumenthal, with their boundary-pushing creations, showcased the limitless possibilities of hydrocolloids. Their dishes, which blurred the lines between science and art, have left an indelible mark on the culinary world, inspiring a new generation of chefs to explore and experiment.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

What are hydrocolloids?

- Hydrocolloids are substances that form gels in the presence of water. They are used in cooking to thicken, stabilize, and gel various dishes.

-

Where did hydrocolloids originate?

- Different hydrocolloids have different origins. For instance, agar originated in China, while locust bean gum has Middle Eastern roots.

-

How have hydrocolloids impacted modern cooking?

- Modern gastronomy, especially molecular cooking, has embraced hydrocolloids to create innovative textures and presentations in dishes.

-

Are hydrocolloids sustainable?

- Many plant-based hydrocolloids are considered sustainable. However, the sustainability of a hydrocolloid also depends on its sourcing and production practices.

-

Are there health benefits associated with hydrocolloids?

- Some hydrocolloids, like pectin and beta-glucans, are being researched for potential health benefits, though it's always essential to consult with health professionals regarding dietary choices.

For further reading: The Power of Sodium Alginate

About the Editor

About the Chef Edmund: Chef Edmund is the Founder of Cape Crystal Brands and EnvironMolds. He is the author of several non-fiction “How-to” books, past publisher of the ArtMolds Journal Magazine and six cookbooks available for download on this site. He lives and breathes his food blogs as both writer and editor. You can follow him on Twitter and Linkedin.

Sources:

- Wang, L. (2003). China's Culinary History. Beijing Press.

- Zhou, M. (2010). The Silk Road Gourmet. Culinary Explorations.

- Thompson, F. (1998). Egyptian Food and Drink. Shire Egyptology.

- Hassan, F. (2002). Traditional Foods and Beverages of Ancient Egypt. Cairo University Press.

- Smith, P. (2004). The Science of Cooking. Springer.

- Johnson, A. (2011). The Renaissance Kitchen. Culinary Historians Press.

- Rossi, M. (2015). Gelatin in the Renaissance Cuisine. Gastronomy Today.

- Dupont, J. (1999). The Essence of French Cooking. Parisian Press.

- Lebovitz, D. (2010). The Sweet Life in Paris. Delacorte Press.

- Bernard, L. (2007). Preserving France. Canning Classics.

- Wells, P. (2005). The Food Lover's Guide to Paris. Workman Publishing.

- Adrià, F. (2008). A Day at El Bulli. Phaidon Press.

- Soler, J., & Adrià, A. (2014). elBulli 2005-2011. Phaidon Press.

- Blumenthal, H. (2008). The Big Fat Duck Cookbook. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Ruhlman, M., & Blumenthal, H. (2013). Heston Blumenthal at Home. Bloomsbury Publishing.

|

About the Author Ed is the founder of Cape Crystal Brands, editor of the Beginner’s Guide to Hydrocolloids, and a passionate advocate for making food science accessible to all. Discover premium ingredients, expert resources, and free formulation tools at capecrystalbrands.com/tools. — Ed |

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.